In oral communication, the speaker's degree of foreign accent is the (first) anchor point perceived by the native listeners. It is the space of orality where perception of deviations occurs. The phenomenon one states as foreign accent is a complex aspect of language that affects speakers and listeners both in production and perception and, consequently, in social interaction. Foreign accent depends on two great domains in Phonetics: the segmental domain (vocalic- and consonantal-related parameters) and the prosodic domain (stress, rhythm, intonation, and voice quality parameters that we will focus henceforth). As the literature has pointed out and covered to some extent, it is not difficult to come across phonetic problems related to L2 prosody. But what is Prosody then?

In a broad sense, Fletcher (2010), and Jackson and O’Brien (2011) pose that many phoneticians and speech scientists define Prosody or prosodic features as synonymous of variations in suprasegmental parameters in the paralinguistic domain such as duration, F0 and intensity that contribute in various combinations to the production and perception of stress, rhythm and tempo, lexical tone, and intonation besides voice quality of an utterance that cannot necessarily be reduced to individual consonants and vowels but generally extend across several segments towards syllabic and higher units. Barbosa (2012, 2019) states that Prosody is the product of an optimal solution between constraints on regularity of the production system and constraints on distinctiveness of the perception system, organized as a function of time, not mandatorily congruent to syntax, that is to say, the syntactic and prosodic elements are not necessarily aligned in the utterance.

In the domain of L2 prosody, phonetic literature has based on a possible connection between the use of (non-)nativelikeness prosodic cues in L2 speech production (and perception), this (non-)nativelikeness includes the features aforementioned by Fletcher (2010), and Jackson and O’Brien (2011) (stress, rhythm, intonation, voice quality, etc.). Deviations or inadequate production of L2 prosody can lead to misunderstandings on both semantic and pragmatic domains.

L2 stress

Stress refers to the durational and intensive prominence of a given syllable in a word (lexical stress) or in an utterance (phrase stress). For example, in English, the lexical stress can act to differentiate word classes, such as for the noun <PROgress>, where stress locates on the first syllable, and for the verb <proGRESS>, where it is located on the second syllable. L2 speakers that do not present this exact pattern in their L1, such as Brazilian Portuguese (BP) speakers, may confuse stress position in homographs such as the ones above mentioned. Moreover, Hewings (2007), Hancock (2012), and Carley and Mees (2020) state that two distinct acoustic correlates operate in the prosodic level of English: stress, determined by duration, right-located from the prosodic boundary, and pitch accent, determined by F0, left-located from the prosodic boundary. For instance, BP speakers of English present difficulties in the perception and the production of the English stress (lexical or phrase) and pitch accent because of the speakers’ L1 pattern based on intensity and duration right-located of the prosodic boundary for both correlates, as attested by Modesto (2019).

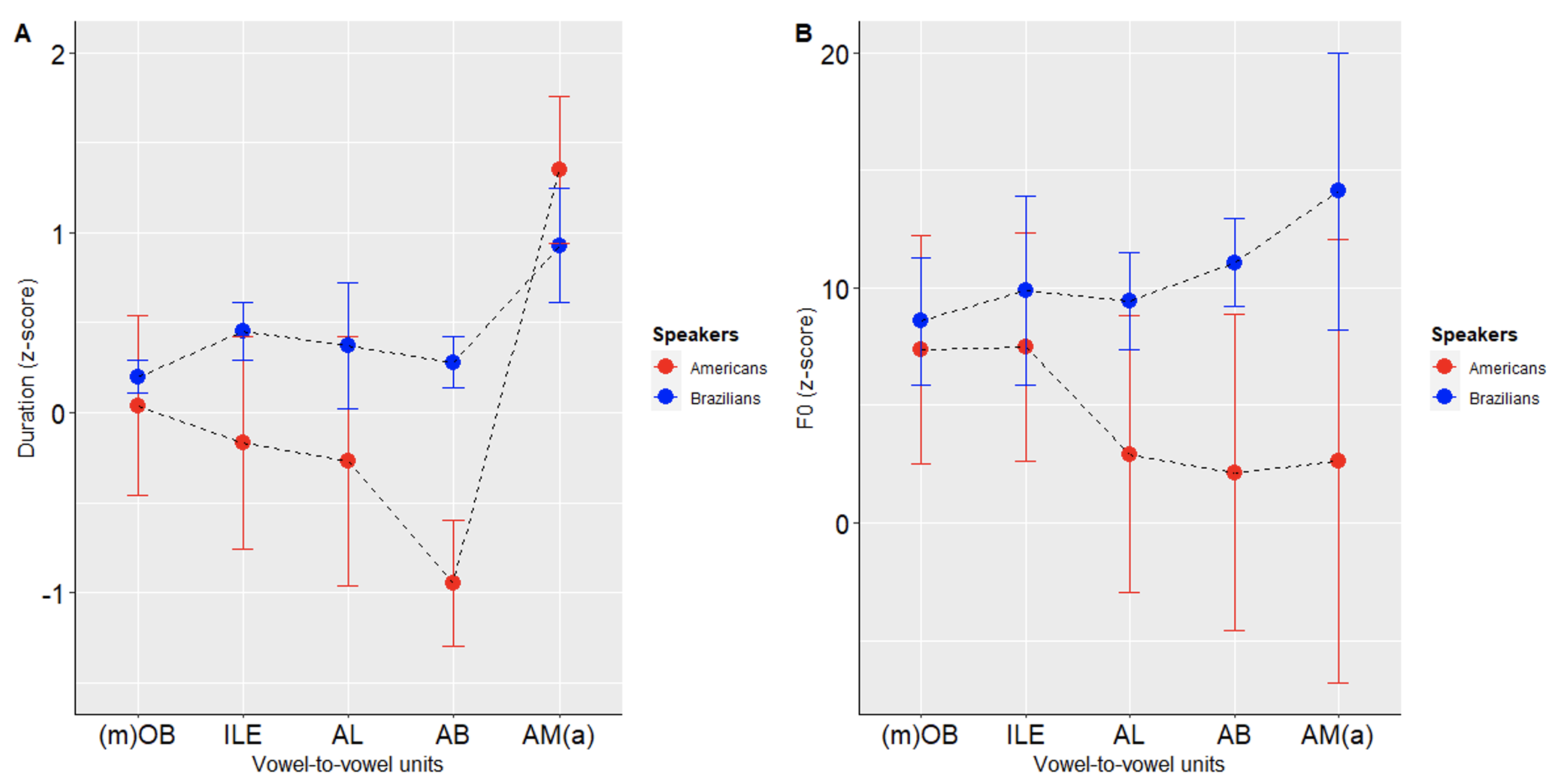

For stress, on the one hand, native speakers of American English (AmE) decrease significantly unstressed syllable duration and consistently increase the phrase stress syllable when producing English utterances, and for pitch accent, speakers increase F0 range on the left-located syllable/s of the prosodic boundary and negatively tilt the trajectory the closer it sets to the phrase stress. On the other hand, for both stress and pitch accent, BP speakers tend to maintain a similar pattern for the correlates, that is, duration and F0 relatively increase in phrase stress syllable positively tilting the F0 trajectory towards stress position (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 presents duration and F0 of both L1-L2 English stress and pitch pattern extracted from the production of eight native AmE speakers, and eight BP speakers of English. Both duration and F0 were normalized into Lobanov’s method (z-score, LOBANOV, 1971) for the preservation of the perceptual-related most prominent syllabic unit (for duration. See thorough discussion in Barbosa, 2006) other than reduction of diferences between male/female vocal folds (for F0. See Barbosa and Madureira, 2015 for details):

Figure 1: Duration (panel A) and F0 (panel B) mean of V-V units for the English sentence <Mobile, Alabama> produced by native and BP speakers of English. Whiskers indicate standard deviation.

L2 rhythm

According to Dafydd (2021): “Rhythm is easy to recognize. One can feel it, hear it and see it, in music, in dance, in walking and running, in speech, in singing, in heartbeats, in the ticking of a clock”. For speech purposes, Barbosa and Bailly (1994) propose that rhythm is the sensation caused by the succession of different degrees of syllabic prominence alternated with non-prominent syllables throughout the utterance. With respect to L2 speech rhythm, phonetic literature has laid on different parameters for its characterization. Following L1 rhythmic categorization fashion for languages as being stress-timed or syllable-timed, L2 rhythm was then similarly categorized based on the speaker’s L1, that is to say, L2 speakers of English whose L1 is categorized as syllable-timed, would transfer rhythmic features to the target-L2.

Since the 1990s a great deal of the literature on L2 rhythm have been based on parameter-like procedures (see Fuchs, 2016 for an outline of the literature and procedural techniques). The use of the so-called rhythm metrics (bi-dimensional models based on mathematical formulae established as cartesian coordenates, which in their vast majority, are based on vocalic and consonantal segments) have been largely applied to measure L2 rhythm and determine whether languages are more or less syllable-/stress-timed, and more recently, the use of prosodic-acoustic parameters, which are based on centrality, variability and dynamics of prosodic units (see Silva Jr. and Barbosa, 2019 for the impact of both rhythm metrics and prosodic-acoustic parameters).

L2 intonation

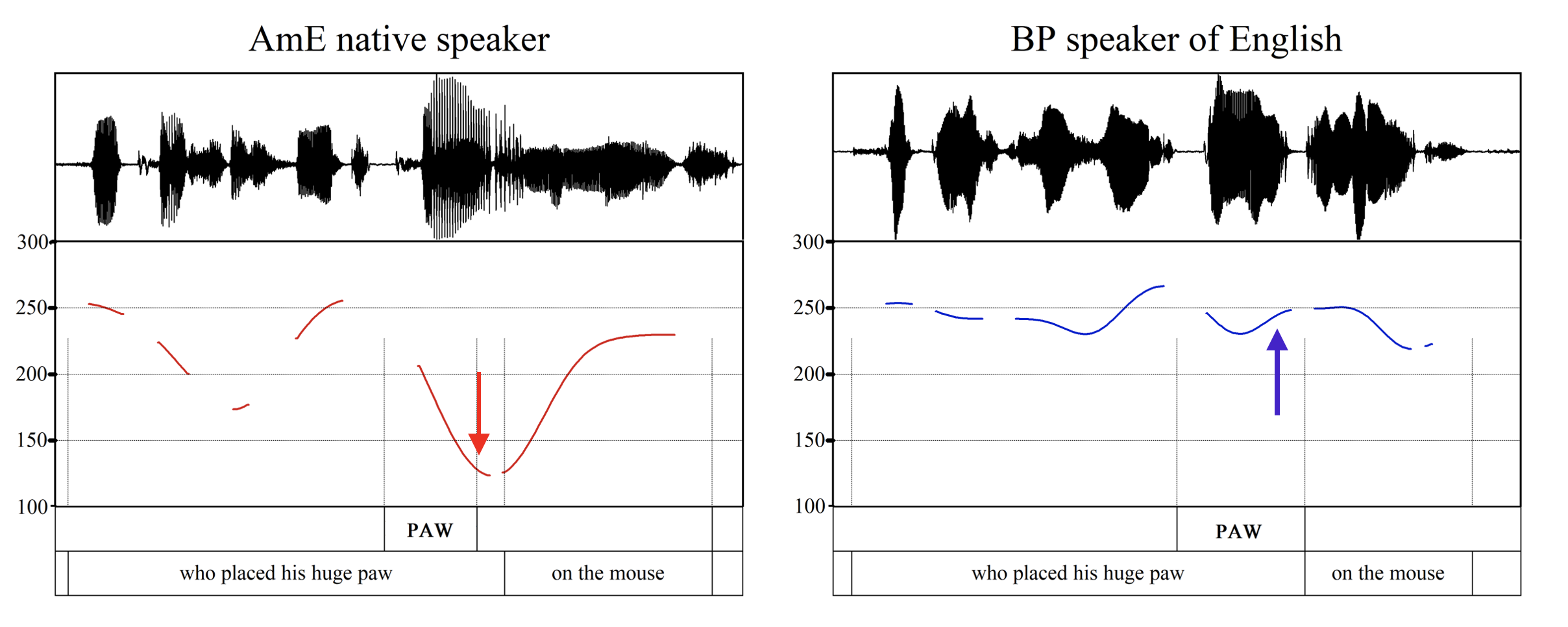

Intonation refers to the pitch variation perceived by the speaker in an utterance. Acoustically, it refers to the contour of the speaker's F0. In English and BP, for example, F0 can be ascending indicating a yes/no question and descending indicating an assertion or a wh-question. Moreno (2000) considers L2 intonation one of the most difficult aspects to be perfromed by foreign speakers. For the author, during pronunciation teaching, intonation is considered, at best, to be something irrelevant due to the priority given to the segmental domain. Reed and Michaud (2015) also severe that on daily pronunciation classes, students, consciously or unconsciously, do not realize L2 intonation patterns, a fact that makes them distant from the pragmatic-discursive meanings detected by melodic variation of the intonational gestures. Mennen et al. (2008, 2012), Urbani (2012), Silva Jr. and Barbosa (2019, 2020) for German, Italian and BP speakers of English respectively, found significantly higher F0 range and melodic variation in English-L1, rather than in English-L2. Silva Jr. and Barbosa’s study yet found a shift of the F0 movement when it reaches phrase stress position. Figure 2 presents L1-L2 intonational diferences of an English sentence:

Figure 2: Waveform and F0 contour of the utterance: <who placed his huge PAW on the mouse> spoken by both a native (red F0 contour on the left panel) and a BP (blue F0 contour on the right panel) speaker of English. Arrows indicate contour shift in phrase stress

Source: Adapted from Silva Jr. and Barbosa (2019, 2020).

L2 voice quality

According to Laver (1980) and Esling et al. (2019), in the broadest theoretical sense, voice quality is a phonetic descriptor and refers to the result of the long-term use of the vocal tract in distinct laryngeal configurations that characterize the voice of a given speaker and that, perceptually, attribute “color” to a certain L2 accent. Laver assumes that some speakers make mutiple larygeal adjustments such as higher/lower pitch, breathy/creaky/whispering voices, etc in a way that speech becomes affected. According to Esling and Wong (1983), and Derwing and Munro (2015), when speakers of an L2 transfer vocal quality from their L1, the result is perceived as a foreign accent by native speakers. Derwing and Munro argument that there is no robust scientific evidence whether voice quality does indeed alter the foreign accent to the point where the speaker becomes unintelligible. Moyer (2013) states that the L2 voice quality aligned to prosody (especially intonation) represents a stereotype from the perception of native speakers, such as intelligence, confidence, ambition, sincerity, reliability, sympathy, insecurity, etc., however, L2 speakers run the risk of committing intercultural context-based misunderstandings.

L2 Prosody and Pronunciation Teaching

Pennington (1989), asserts that the teaching of pronunciation must adopt an integrated approach that prioritizes L2 prosody such as, the inclusion of parameters related to voice quality, rhythm, intonation and intensity. Celce‐Murcia, et al. (2010) point out that learners from a syllable-based language background will present, at least to some extent, considerable difficulties in assigning greater length to the stressed syllables of content words within a sentence. The authors also emphasize that stress‐based rhythm helps to improve English-L2 speech fluency of learners whose L1 is syllable-based, and they yet implement L2 prosody features to be some of the major structures that native speakers rely on when assessing and estabilishing criteria of foreign accent and its degree.

Low (2015) suggests that teachers should be aware of learners’ motivation towards a globalist orientation, that is, “stress‐based rhythm” should be taught, and towards a localist orientation, where “syllable‐based rhythm” should be the focus of the pronunciation classroom. Aligned to Celce-Murcia and colleagues, and Low above cited, Ghanem and Kang (2018) assert that many speaking features have been shown to predict L2 speakers’ proficiency level and/or cue foreign accentedness and, what seems to be trustful in terms of assessment of foreign accent is piped by L2 prosody features and these features shall be highlighted in pronunciation classes.

L2 Prosody and Forensics

In addition to what we have seen so far about L2 prosody and its applications, one of the facets of its use would be in Forensic Phonetics for speaker identification via foreign accent.

L2 prosodic features can be found in duration-, F0- and intensity-related acoustic parameters, voice quality, as well as to the way we breathe. In practice, such parameters are reflected in the slope (increase/decrease contour) of the F0, intensive vocal effort, changes in voice quality, speech rate, amplitude-modulated breathing, and so many parameterss to be described. A very fluent L2 speaker may disguise the prosodic agenda in one’s favour by modifying some features of the foreign accent as proposed by Farrús (2008, 2018). The use of techniques such as voice lineups – allowed in some countries as the U.S., Great Bratain, Australia, etc. - has been a trend among specialists to draw inferences about foreign accent identification in prosecutions (see Broeders and Rietveld, 1995 for an introductory-detailed discussion).

Acknowledgments

I would gratefully like to thank Professors Tommaso Raso and Plínio Brabosa for the invitation to write this entry about L2 Prosody; I also thank Professor Plínio Barbosa for his fruitful comments and suggestions. Yet I gratefully acknowledge the grant from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, BRAZIL) nº. 151027/2020-0.

References

BARBOSA, P. (2019). Prosódia. São Paulo: Parábola.

BARBOSA, P. (2012). Conhecendo melhor a prosódia: aspectos teóricos e metodológicos daquilo que molda nossa enunciação. Revista de Estudos da Linguagem., v. 20, n. 1, p. 11-27.

BARBOSA, P. (2006). Incursões em torno do ritmo da fala. Campinas, FAPESP/Pontes Editores.

BARBOSA, P.; BAILLY, G. (1994). Characterisation of rhythmic patterns for text-to-speech synthesis, Speech Communication, v. 15, p. 127-137.

BARBOSA, P.; MADUREIRA, S. (2015). Manual de Fonética Acústica Experimental: aplicações a dados do português. São Paulo: Cortez.

BROEDERS, A. P; RIETVELD, A. (1995). Speaker identification by earwitnesses. In: BRAUN, A.; KOSTER, J-P. (Eds) Studies in Forensic Phonetics. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher V erlag, p. 24–40.

CARLEY, P.; MEES, I. (2020). American English Phonetics and Pronunciation Practice. Routledge.

CELCE-MURCIA, M.; BRINTON, D.; GOODWIN, J. (2010). Teaching Pronunciation: A course book and reference guide, 2 ed. New York, Cambridge University Press.

DERWING, T.; MUNRO, M. (2015). Pronunciation Fundamentals: Evidence-based perspectives for L2 teaching and research. Amsterdan: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

ESLING, J.; MOISIK, S.; BENNER, A.; CREVIER-BUCHMAN, L. (2019). Voice Quality: The Laryngeal Articulator Model. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ESLING, J.; WONG, R. (1983). Voice Quality Settings and the Teaching of Pronunciation. TESOL Quarterly, v. 17, n.1, p. 89-95.

FARRÚS, M. (2018). Voice Disguise in Automatic Speaker Recognition. ACM Computing Surveys, n. 4, v. 51, p. 1-22.

FARRÚS, M. (2008). Fusing prosodic and acoustic information for speaker recognition. The International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law, v. 16, n.1.

FLETCHER, J. (2010). The Prosody of Speech: Timing and Rhythm. In: HARDCASTLE, W.; LAVER, J.; GIBBON, F. The Handbook of Phonetic Sciences, 2 ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, p. 523-602.

FUCHS, R. (2016). Speech Rhythm in Varieties of English: Evidence from Educated Indian English and British English. Dordrecht: Springer.

GHANEM, R.; KANG, O. (2018). Pronunciation features in rating criteria. In: KANG, O. GINTHER, A. (Eds.). Assessment In Second Language Pronunciation. New York: Routledge, p. 115-136.

GIBBON, D. (2021). Speech Rhythm. In: Verbetes LBASS. Available at: http://www.letras.ufmg.br/lbass/.

HANCOCK, M. (2012). English Pronunciation in Use: intermediate. Cambridge: Cambrdge: University Press.

HEWINGS, M. (2007). English Pronunciation in Use: advanced. Cambridge: Cambrdge: University Press.

JACKSON, C.; O'BRIEN, M. (2011). The interaction between prosody and meaning in second language speech production. Die Unterrichtspraxis:Teaching German, v. 44, n. 1, p. 1-9.

LAVER, J. (1980) The Phonetic Description of Voice Quality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

LOBANOV, B. (1971). Classification of Russian Vowels Spoken by Different Speakers. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, v. 49, n. 2B, p. 606-609.

LOW, E. (2015). The Rhythmic Patterning of English(es): Implications for Pronunciation Teaching, In: REED, M.; LEVIS, J. (Eds). The Handbook of English Pronunciation. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 125-138.

MENNEN, I.; SCHAEFFER, F.; DOCHERTY, G. (2008). A methodological study into the linguistic dimensions of pitch range differences between German and English. In: Proc. 4th Speech Prosody, University of Campinas, p. 527-530.

MENNEN, I.; SCHAEFFER, F.; DOCHERTY, G. Cross-language difference in F0 range: a comparative study of English and German. JASA, v. 131, n. 3, p. 2249-2260.

MODESTO, F. Acoustic analysis of lexical stress in English by Brazilian Portuguese speakers, and inferences of production and perception. Dissertation (Master in Science). Institute of Language Studies, University of Campinas, Campinas, 2019.

MORENO, M. (2000). Sobre la adquisición de la prosodia en lengua extranjera: Estado de la cuestión. Didáctica. Lengua y Literatura, p. 91-119.

MOYER, A. (2013). Foreign Accent: The Phenomenon of Non-native Speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

PENNINGTON, M. (1989). Teaching pronunciation from the top down. RELC Journal, v. 20, p. 20–38.

REED, M. MICHAUD, C. (2015). Intonation in Research and Practice: The Importance of Metacognition. In. M. Reed; J. Levis. (Orgs). The Handbook of English Pronunciation. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, p.454-470.

SILVA JR., L; BARBOSA, P. (2020). Speech Rhythm of English as L2: the influence of duration and F0 on foreign accent investigation. Anais do I Congresso Brasileiro de Prosódia, v. 1, p 59-62. Available at: <http://www.periodicos.letras.ufmg.br/index.php/anais_coloquio>.

SILVA JR., L; BARBOSA, P. (2019). Speech Rhythm of English as L2: an investigation of prosodic variables on the production of Brazilian Portuguese speakers. Journal of Speech Sciences, v. 8, n. 2, p. 37-57, 2019. Available at: <http://revistas.iel.unicamp.br/joss>.

URBANI, M. (2012). Pitch Range in L1/L2 English. An Analysis of F0 using LTD and Linguistic Measures. Padova: Coop. Libraria Editrice Università di Padova.

SUGGESTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Introductory L2 Prosody

DELAIS-ROUSSARIE, E.; AVANZI, M.; HERMENT, S. (2015). Prosody and Language in Contact: L2 Acquisition, Attrition and Languages in Multilingual Situations. Berlin: Springer.

FLETCHER, J. (2010). The Prosody of Speech: Timing and Rhythm. In: HARDCASTLE, W.; LAVER, J.; GIBBON, F. The Handbook of Phonetic Sciences, 2 ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, p. 523-602.

FUCHS, R. (2016). Speech Rhythm in Varieties of English: Evidence from Educated Indian English and British English. Dordrecht: Springer.

LOW, E. (2015). The Rhythmic Patterning of English(es): Implications for Pronunciation Teaching, In: REED, M.; LEVIS, J. (Eds). The Handbook of English Pronunciation. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 125-138.

MOYER, A. (2013). Foreign Accent: The Phenomenon of Non-native Speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

NOOTEBOOM, S. (1997). The Prosody of Speech: Melody and Rhythm. In. HARDCASTLE, W.; LAVER, J. GIBBON, F. (Orgs). The Handbook of Phonetic Sciences, Utrecht: Utdallas.Edu.

THOMPSON, I. (1991). Foreign accents revisited: The English pronunciation of Russian immigrants. Language Learning, v.41, p. 177-204.

TROUVAIN, J.; GUT, U. (2007). Non-Native Prosody: Phonetic Description and Teaching Practice. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Advanced L2 Prosody

BAUS, C.; MCALEER, P.; MARCOUX, K.; BELIN, P.; COSTA, A. (2019). Forming social impressions from voices in native and foreign languages. Nature, v. 414, n. 9, p. 1-17.

DELLWO, V. (2008). The role of speech rate in perceiving speech rhythm. In. Proceedings of speech prosody 2008, Campanela, p. 375–378.

DELLWO, V. (2006). Rhythm and speech rate: A variation coefficient for deltaC. In Language and language-processing proceedings of the 38th linguistics colloquium, ed. Pawel Karnowski and Imre Szigeti, p. 231–241. Frank-furt am Main: Peter Lang.

DETERDING, D. (2001). The measurement of rhythm: A comparison of Singapore and British English. Journal of Phonetics, v. 29, p. 217–230.

GIBBON, D.; GUT, U. (2001). Measuring speech rhythm. In. Proceedings of Eurospeech 2001, Aalborg, p. 91–94.

GRABE. E; LOW, E. (2002). Durational variability in speech and the rhythm class hypothesis. In: GUSSENHOVEN, C.; WARNER, N, (Eds.). Papers in Laboratory Phonology, v, 7, Berlin: Mouton, p. 515–546.

LOW, E., GRABE, E.; NOLAN, F. (2000). Quantitative characterization of speech

rhythm: Syllable-timing in Singapore English. Language and Speech, v. 43, n. 4, p. 377–401.

RAMUS, F.; NESPOR, M.; MEHLER, J. (1999). Correlates of linguistic rhythm in the speech signal. Cognition, v. 73, p. 265–292.

SILVA JR., L; BARBOSA, P. (2020). Speech Rhythm of English as L2: the influence of duration and F0 on foreign accent investigation. Anais do I Congresso Brasileiro de Prosódia, v. 1, p 59-62. Available at: <http://www.periodicos.letras.ufmg.br/index.php/anais_coloquio>.

SILVA JR., L; BARBOSA, P. (2019). Speech Rhythm of English as L2: an investigation of prosodic variables on the production of Brazilian Portuguese speakers. Journal of Speech Sciences, v. 8, n. 2, p. 37-57, 2019. Available at: <http://revistas.iel.unicamp.br/joss>.

WAGNER, P.; DELLWO, V. (2004). Introducing YARD (yet another rhythm determination) and re-introducing isochrony to rhythm research. In Proceedings of Speech Prosody 2004. ISCA, 227–230.

WHITE, L.; MATTYS, L. (2007). Calibrating rhythm: First language and second language studies. Journal of Phonetics. v. 35, n. 4, p. 501–522.

Forensic L2 Prosody

DAS, A.; ZAO, G.; LEVIS, J. CHUKHAREV-HUDILAINEN, E.; GUTIERREZ-OSUNA, R. (2020). Understanding the Effect of Voice Quality and Accent on Talker Similarity. In: Proceedings of Interspeech, p. 1763-1767.

FARRÚS, M. (2018). Voice Disguise in Automatic Speaker Recognition. ACM Computing Surveys, n. 4, v. 51, p. 1-22.

FARRÚS, M. (2008). Fusing prosodic and acoustic information for speaker recognition. The International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law, v. 16, n.1.

Goggin, J.; Thompson, C.; Strube, G.; Simental, L. (1991) The role of language familiarity in voice identification. Memory and Cognition, v. 19, p. 448–458.

ROGERS, H. Foreign accent in voice discrimination: a case study. Forensic Linguistics, n. 5, v. 2, p. 203-208, 1998.

SCHILLER, N.; KÖSTER, O.; DUCKWORTH, M. (1997) The effect of removing linguistic information upon identifying speakers of a foreign language, Forensic Linguistics, v. 4, n. 1, p. 1–17.

L2 Prosody and Expressivity

DE MARCO, A. (2020). Teaching the Prosody of Emotive Communication in a Second Language. In. SAVVIDOU, C. (Ed.). Second Language Acquisition: Pedagogies, Practices and Perspectives. London: IntechOpen, p. 1-18.

RILLIARD, A.; ERICKSON, D.; DE MORAES, J.A.; SHOCHI, T. (2017). Perception of expressive prosodic speech acts performed in USA English by L1 and L2 speakers. Journal of Speech Sciences, v. 6, n. 1, p. 27-45. Available at: <http://revistas.iel.unicamp.br/joss>.

L2 Prosody Teaching

LEVIS, J. (2018). Intelligibility, Oral Communication and the Teaching of Pronunciation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SILVA JR., L.; BARBOSA, P. (2021). Efeitos da Prosódia de L2 no ensino de pronúncia e na comunicação oral. Prolíngua, v. 16, n.1, (IN PRESS).

SAVVIDOU, C. (2020). Second Language Acquisition: Pedagogies, Practices and Perspectives. London: IntechOpen.