Paralinguistics is defined ex negativo: It is not linguistics but ‘alongside linguistics’ (from the Greek preposition παρα). Its subject area is not phonetics, grammar, or semantics ‘as such’; it is not about what you say but how you say something. It is about connotations and not about denotations: A denotation of a word is its literal, primary meaning (‘plain’ semantics) that can be found in a simple dictionary; a connotation of a word is everything what else is meant by it – i. e., positive, neutral, or negative valence. We can expand ‘word’ onto any chain of words, and onto vocal productions that do not have a clear denotation but only connotations. Another way of contrasting the two aspects could be to tell apart semantic meaning from affective meaning; see affectivism (Dukes, Daniel and Abrams, Kathryn and Adolphs, Ralph et al. 2021).

Linguists of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century were not especially interested in paralinguistics: “The investigation of socially effective but non-distinctive patterns in speech, an investigation scarcely begun, concerns itself, accordingly, to a large extent with pitch.” (Bloomfield 1933, p. 114). This turned into plain disinterest with the advent of structural and generative linguistics and, as far as speech is concerned, on formal aspects within phonetics and phonology. Moreover, automatic speech and language processing, starting in the middle of the last century, focused at the beginning as well on what had been said or written down, not on its connotations.

Although the term ‘paralanguage’ has been already introduced, according to Trager (1958), by the American linguist Archibald Hill (Hill 1958), and paralinguistics has been propagated by, amongst others, David Crystal (1971, 1974), it took some time until it evolved into an umbrella term, denoting a broad field, for everything that has to do with connotations instead of denotations. In the meantime, paralinguistic topics were dealt with as well by related fields such as pragmatics, ethnography of communication, socio- and psycholinguistics, or sociology and psychology. As a reaction to an emphasis on verbal communication, the field of Nonverbal Communication emerged in the 1960ies (Jones & LeBaron 2002).

We define paralinguistics as the field that models the human ability to communicate, beyond denotations, connotations (valence) with written or spoken language, or with vocal productions. Note that this also entails soliloquies (monologues) that principally can be overheard and recorded, following the maxim ‘you cannot not communicate’ (Watzlawick et al. 1967).

In Fig. 1, we present a feature model for defining paralinguistics and non-verbal communication and for telling the two fields apart, employing the binary features [vocal], [verbal], [dynamic], and [distant], and focusing on the individual that communicates. Paralinguistics pertains to (para-)language: (1) in the written modality, i. e., [-vocal,+verbal]; (2) in the spoken modality (speech): [+vocal,+verbal]; and (3) in more or less nonverbal productions: [+vocal,-verbal]. Short descriptions and examples are given in the column ‘sub-domain/phenomena’. Whereas paralinguistics is always [±dynamic,-distant] – features can be constant or change rapidly but describe the vocal signals produced by the speaker or its written equivalent, non-verbal communication is always [-vocal,-verbal]: Characteristics of the body are modelled, with different combinations of the binary values for [dynamic] and [distant], and within different modalities, communicated over different channels; terms are mostly taken from Burgoon et al. (2022). Most researched is arguably body kinesis.

Alternatives are a narrower and a very broad definition of paralinguistics – not advocated by us, see Fig. 1: The narrower definition is represented by the green part of the field ‘para-linguistics’; only [+ vocal] features, be this non-verbal vocalisations embedded within/between speech, or be this features modulated onto spoken language. The very broad definition is represented by the green part across the two fields non-verbal communication and para-linguistics, besides the [+vocal] features everything else apart from [-vocal,+verbal], i. e., [-vocal,-verbal]. The narrower definition disregards the tight links between phonetics and linguistics; the very broad definition is simply not necessary and spans over too many modalities. Thus it makes sense to confine paralinguistics to the two modalities audio and writing. Further information can be found in chapter 1 of Schuller & Batliner (2014).

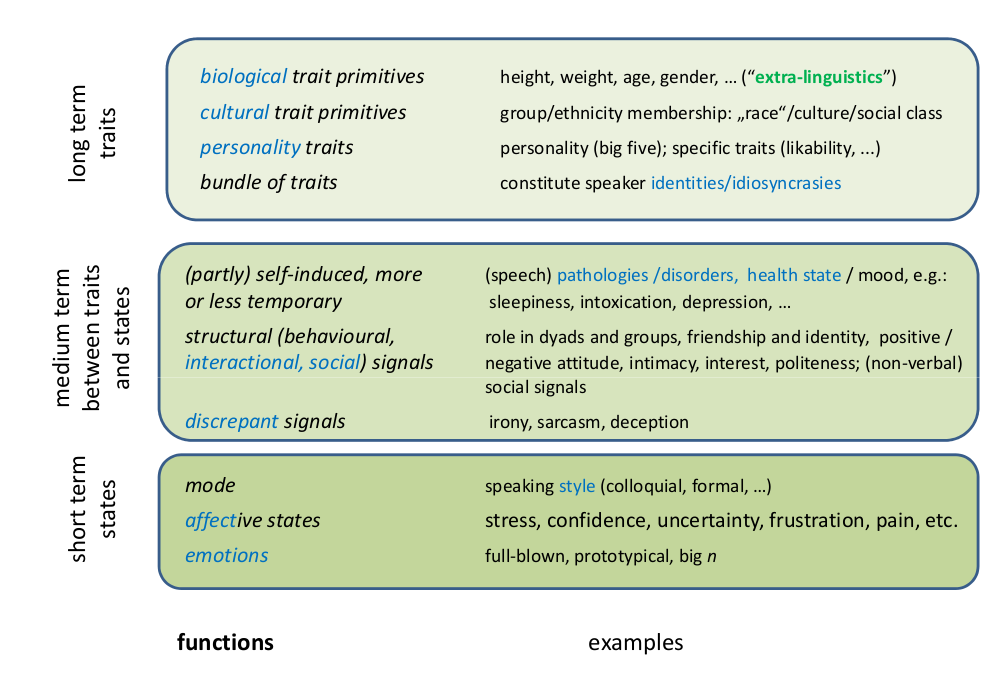

Fig. 2 lists the functions that can be denoted within paralinguistics. There are typical functions addressed rather often: full-blown emotions, depression, traits such as likability or charisma. There are less typical ones such as non-native accent or dialectal traits that can as well be attributed to the realm of linguistics, not paralinguistics. However, we cannot find a definiens that strictly tells apart these two object ranges – neither formal ones nor functional ones. Note that the tri-partitioning into long term, medium term, and short term is based on (proto-)typicality. Even ‘extra-linguistic’ biological trail primitives can change during the life-span – think of gender fluidity. On the other hand, short term states such as confidence can be as well a persistent trait of an individual.

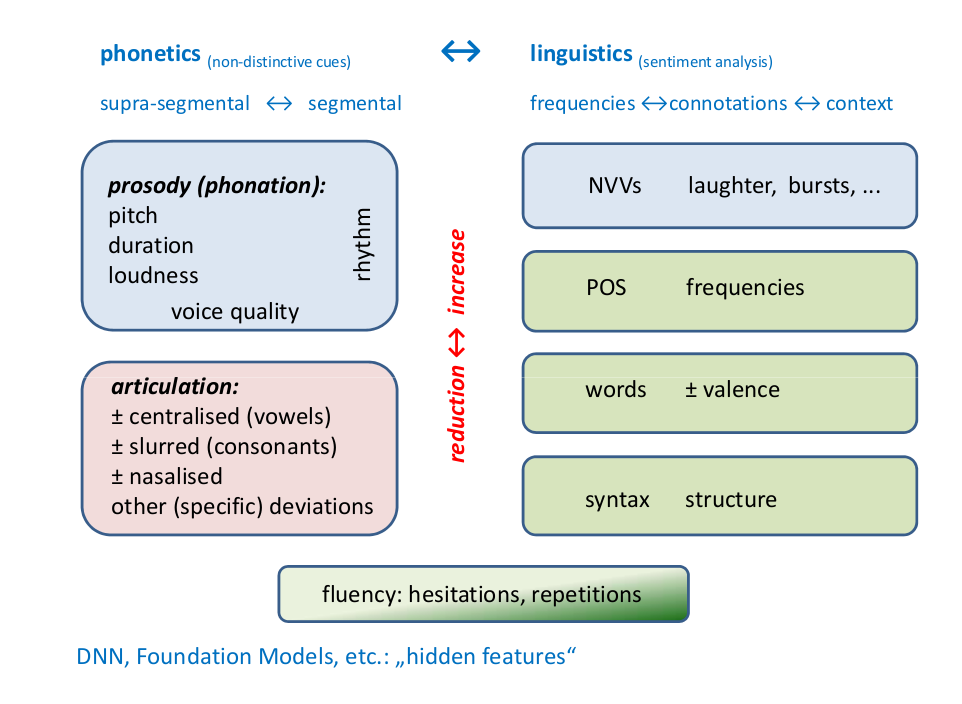

Fig. 3 lists the formal means within paralinguistics; basically, these are the same as within ‘standard’ phonetics and linguistics. They can denote different functions when they differ from a default use. This default use and the deviation is (not only) ‘in the eye of the beholder’ – whether they interpret it as idiosyncratic, group characteristics, pathological, etc. Fig. 3 is an attempt to display the most important formal means in one figure that are dealt with in phonetics – when the cues are linguistically non-distinctive, and in linguistics – the broad field of sentiment analysis. When we do not explicitly model paralinguistics with these cues within artificial intelligence (AI) approaches such as deep neural networks (DNNs) and foundation models, no features are used, i. e., they are hidden and (equivalents) can only be made visible by additional attempts within explainable AI. To the left, we find prosodic means that can be attributed to phonation – the ‘classic’ three parameters pitch, duration, and loudness that together constitute rhythm; voice quality as the – less ‘classic’ – fourth dimension (Campbell & Mokhtari 2003) in between prosody and articulation; and articulatory means – most important amongst these are maybe the centralisation of vowels and slurred speech that mostly pertains consonants. This is typical for pathological speech but can as well characterise, e. g., sociolects or other medium and short term states and traits. Whereas (macro-)prosody per se is supra-segmental, apart from micro-prosody which is treated as well as belonging to one segment, the term articulation might be used for one segment. However, when it is a global trend, then we have to speak about supra-segmental articulatory characteristics. To the right, linguistic means are displayed: Normally, frequencies are counted and connotations (positive or negative valence) are modelled. Often, the context defines the specific function. We list four types, beginning with NVVs (nonverbal vocalisations), then POS (part-of-speech), words, and syntax. A fifth type, characterised by both phonetics and linguistic means, is fluency with hesitations (filled/unfilled pauses, lengthening) and repetition.

Trivially, it is always about a ‘more or less’, i. e., about increase (of feature values or frequencies) or decrease, such as lower or higher pitch, or less or more function words.

Note that there is not a set of features – be these acoustic-prosodic or linguistic features – that exclusively models paralinguisic phenomena. Regardless of which features (characteristics) we observe: When we see a systematic difference between one individual and other individuals or a group of individuals that share a common characteristic, we can harness this feature for paralinguistics. Thus, Fig. 3 is not exhaustive but lists the most important and most frequently employed features.

A more detailed account of formal means employed in paralinguistics and of the different functions can be found in part I of Schuller & Batliner (2014); as for ethical considerations, both for basic and applied research, see Batliner et al. (2022, 2023).

Batliner, A., Hantke, S. & Schuller, B. (2022), ‘Ethics and good practice in computational paralinguistics’, IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 13(3), 1236–1253.

Batliner, A., Neumann, M., Burkhardt, F., Baird, A., Meyer, S., Vu, N. T. & Schuller, B. W. (2023), ‘Ethical awareness in paralinguistics: A taxonomy of applications’, International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 39(9), 1904–1921.

Bloomfield, L. (1933), Language, Holt, Rinhart and Winston, New York. British edition 1935, London, Allen and Unwin.

Burgoon, J. K., Manusov, V. & Guerrero, L. K. (2022), Nonverbal Communication, Routledge, New York, NY.

Campbell, N. & Mokhtari, P. (2003), Voice Quality: The 4th Prosodic Dimension, in ‘Proc. 15th ICPhS’, Barcelona, Spain, pp. 2417–2420.

Crystal, D. (1971), Prosodic and paralinguistic correlates of social categories, in E. Ardener, ed., ‘Social anthropology’, Tavistock, London, pp. 185–206.

Crystal, D. (1974), Paralinguistics, in T. Sebeok, ed., ‘Current trends in linguistics 12’, Mouton, The Hague, pp. 265–295.

Dukes, Daniel and Abrams, Kathryn and Adolphs, Ralph et al. (2021), ‘The rise of affectivism’, Nature Human Behaviour 5(7), 816–820. URL: http://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01130-8

Hill, A. (1958), Introduction to linguistic structures: from sound to sentence in English, Harcourt, Brace, New York, NY.

Jones, S. E. & LeBaron, C. D. (2002), ‘Research on the relationship between verbal and nonverbal communication: Emerging integrations’, Journal of Communication 52, 499–521.

Schuller, B. & Batliner, A. (2014), Computational Paralinguistics – Emotion, Affect, and Personality in Speech and Language Processing, Wiley, Chichester, UK.

Schuller, B. W., Amiriparian, S., Batliner, A., Gebhard, A., Gerczuk, M., Karas, V., Kathan, A., Seizer, L. & Löchner, J. (2023), ‘Computational charisma—a brick by brick blueprint for building charismatic artificial intelligence’, Frontiers in Computer Science 5. URL: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomp.2023.1135201

Trager, G. L. (1958), ‘Paralanguage: A First Approximation’, Studies in Linguistics 13, 1–12.

Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J. & Jackson, D. D. (1967), Pragmatics of Human Communications, W.W. Norton & Company, New York.